A lot of really crazy ideas were floated as the next big thing during the dot-com bubble. USB-powered olfactory devices, buying 50-pound bags of dogfood online, and even Internet currency backed by Whoopie Goldberg instead of the Fed all got a lot of press and a lot of money before disappearing.

You might remember a lot of excitement around the idea of Internet radio back then too. It seemed for a while that everyone and their brother was setting up RealServer on a spare Pentium II or signing up with Live 365 to broadcast the definitive European house techno mixes or every bootleg Phish MP3 they could collect to the masses. Streaming was dodgy, but possible, over dial-up speeds and it worked so well over high-speed lines that universities and offices ended up blocking ports.

But Internet radio has largely faded away. Was it a bad idea all along, like the CueCat? Nope. Was it killed by ever-expanding iPod storage? Probably not. Rather, Internet radio's popularity and vitality were drained by a poorly-legislated artificial monopoly and compulsory licenses.

This all has to do with how music is licensed. In the wild-west days of the Internet, anyone could broadcast anything and it was up to musicians and copyright holders to go after broadcasters. Since broadcasters included anyone with some spare time and virtually no one was making any money, this resulted in a huge, messy, innovative, fascinating jumble of Internet radio stations, much like the fascinating jumble of Web pages we know and love.

Clearly, though, musicians had a valid argument about not getting paid for their work. At first, the RIAA pursued the same tactic used against Napster and other P2P systems - refuse to negotiate at all and sue into oblivion. Lawsuits, or the threat of lawsuits,

shuttered services like NetRadio.

Finally in 2002 relief came in the form of

uniform royalty rates set by the U.S. Copyright Office. Unfortunately the rate, 7/100th of a cent per song per listener, was much too high for all but the largest Internet broadcasters to pay. And the fee was retroactive to 1998, meaning big checks were due when the policy went in place.

To put that fee into perspective, let's say you have a station that averages 10 listeners at any time. You play songs that average 3 minutes each, and were broadcasting from 1998 through 2002. That's 700,800 songs, and really 7,008,000 listener-songs, which means suddenly you owed almost $5000. Small change for Yahoo, perhaps, but good luck making $5000 in advertising revenue with an audience of 10 listeners.

So by 2002 we've done a great harm to a once promising medium. It isn't dead yet, since some big players can afford the fees or subsidize their broadcasting with other revenue. Not quite dead, but not lively or interesting - let's say five years of a persistent vegetative state.

Now The U.S. Copyright Office is pulling the feeding tube. It has granted the RIAA the

exclusive right to administer a compulsory license over all music through it's collection agency, SoundExchange. This means two things will change- first, the fees are going to go up, way up. Second, even if you don't play any music owned by RIAA member record companies, you still might have to pay them.

This doesn't necessarily benefit the copyright holders. SoundExchange doesn't have to seek out and pay the 13-year-old kid who created some random MP3 on his mom's iMac. Also,

forcing broadcasters out of business will result in less fees being payed.

Pretty much every blog on the Web thinks this is an ill-conceived plan. Listen, I've watched a fair amount of Star Trek in my day and when

Wil Wheaton tells you something won't work, you better listen.

In addition to stunting an entire medium, this whole system is obviously unfair. Internet radio will pay much, much more than terrestrial radio. The regular radio stations pay license fees based on a structure that was calculated based on their revenues.

Those royalties probably totaled less than $500 million last year, but by the time the online fees hit their cap Internet radio will pay a projected $2.3 billion for fewer listeners.

What can you do? Not much, but the

founder of Pandora has asked people to sign a petition. The "Internet Radio Equality Act," introduced by Congressmen Jay Inslee (D-Wash.) and Don Manzullo (R-Ill.), would reverse the decision so writing your Congressmen might help a little.

But in large part the damage is already done. Imagine if the Web had been subject to similar legislation. Back in the 1990s copyright holders like Disney and Fox were aghast that anyone could put up a site with a GIF of Bart Simpson or Mickey Mouse. Do you think the billions of dollars of value and commerce generated by the Web would have happened if every single jpeg, whether or not it was someone else's IP, required payment of .07 cents per pageload?

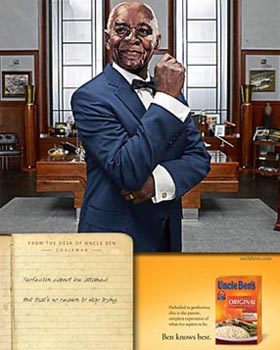

For years, he has been ever with us. A familiar face in the grocery aisle, quick to ease our hunger. But he shall serve you rice no more, for Uncle Ben has been promoted to CEO (or perhaps chairman of the board) of Uncle Ben's Inc.

Uncle Ben, instant rice pitchman, has long been seen as a holdover from less polite times. He clearly was not meant to be your actual uncle, or even that guy your dad knew from school that everyone made you call "uncle" as a creepy sign of pseudo-familiarity and respect.

Since he was an older black man, dressed as either a manservant or perhaps maitre d’, and "uncle" was a disrespectful way to refer to blacks in the South, it seemed perhaps he was just another racist stereotype. Oh, they told us that

For years, he has been ever with us. A familiar face in the grocery aisle, quick to ease our hunger. But he shall serve you rice no more, for Uncle Ben has been promoted to CEO (or perhaps chairman of the board) of Uncle Ben's Inc.

Uncle Ben, instant rice pitchman, has long been seen as a holdover from less polite times. He clearly was not meant to be your actual uncle, or even that guy your dad knew from school that everyone made you call "uncle" as a creepy sign of pseudo-familiarity and respect.

Since he was an older black man, dressed as either a manservant or perhaps maitre d’, and "uncle" was a disrespectful way to refer to blacks in the South, it seemed perhaps he was just another racist stereotype. Oh, they told us that